I went back to school to get my degree in the late ’90s after a lapse in enrollment of 8 years. I ended up becoming pretty friendly with a girl who was in a lot of my classes, she was an older student as well (not as old as I was, but in her mid-twenties), so we started a lot of study groups together because it wasn’t like we were doing cool college kid things like getting drunk and going on road trips or anything.

In getting to know her, I gradually found out that she hadn’t enrolled in college right out of high school because she had moved around the country a lot and never really knew where she was going to end up in any given year, so she would pick up a class or two here and there and that was it. I assumed that maybe she had been in the military, or perhaps her husband or boyfriend was, but I didn’t get too much into it because I figured she’d talk about it if it were relevant.

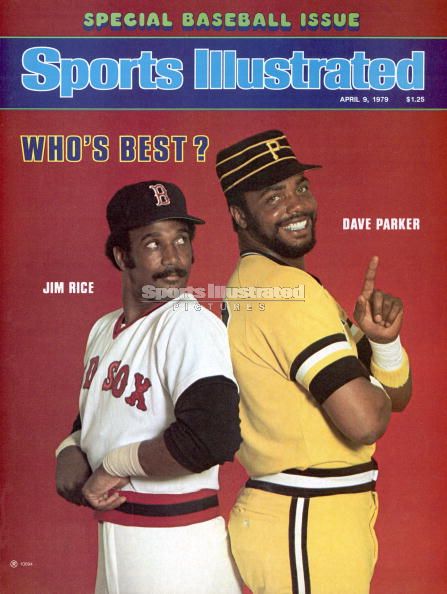

Toward the end of our last semester (spring 2001), during one of our classes I mentioned I had visited Memphis — a friend of mine moved there for a while, somehow it was germane to the topic — and this girl commented that she lived in Memphis for about a year because her husband played baseball there.

“Who, the Chicks?” I asked, referring to Memphis’ Triple-A team.

“Yes. Well, no… they changed to the Redbirds the year he was there. But yes, the same team, basically.” I hadn’t been aware of the change.

“What’s your husband’s name?”

She told me*.

*I don’t want to print his name here, for a variety of reasons, but mostly because I don’t want to single him out. There are millions like him, and his story is symbolic anyway.

I nodded my head in an I-didn’t-know-that fashion, not that I’d have had any reason to know (I had never heard of the guy). She was married, I was soon-to-be engaged, but neither of us talked about our significant others. I didn’t ask any further questions about her husband, because I knew he hadn’t played in the majors by that point, and if she was going to Framingham State College full time I assumed his baseball career was over.

I looked up his stats online the next chance I had. It was a little more difficult to find minor league statistics back then, and I had to go to a few different sites to gather enough info to come close to a complete picture, but a couple of things jumped out at me.

Second round pick out of high school.

28 HR, 106 RBI in High A in 1997.

27 HR, 83 RBI in AA & AAA in 1998.

Then he fell off the table 1999, and was out of baseball after that season (an abortive comeback in Nashville hadn’t happened yet). In looking at his other stats it was clear the guy never hit for average and whiffed a lot, but man, that’s a lot of home runs for the minors.

With this sparse information, I began envisioning some unfortunate injury history, or a backstory that the stats would never illustrate. I sure as hell wasn’t going to ask my friend about it, I’d have felt uncomfortable doing so. We both graduated that spring and kept in touch via email for a little while, but I haven’t had contact with her in quite a few years. But I always remembered her husband’s name, because to me it’s become symbolic for all of the failed careers of former prospects.

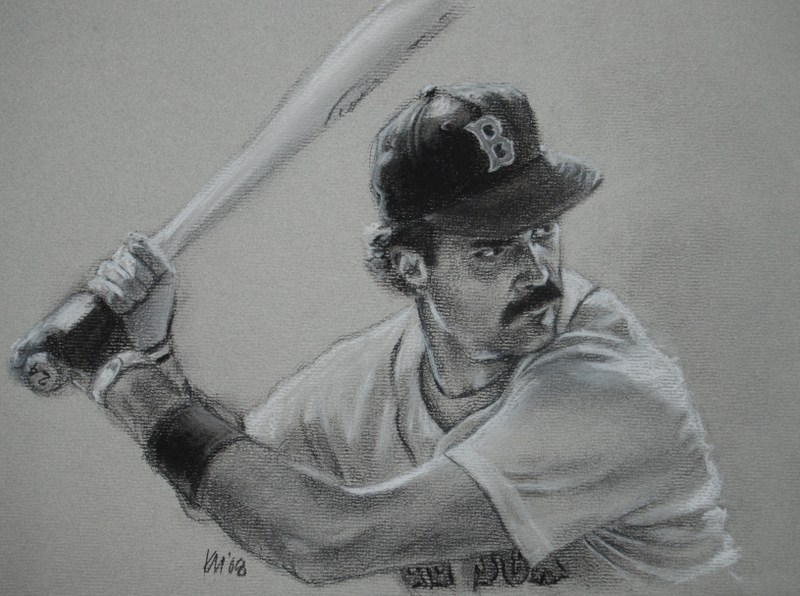

As the web became more saturated with information and search engines became more efficient, this guy’s picture came into sharper focus based on the available numbers alone. Two seasons spent in rookie ball, two in low-A. He was 22 before he ever even got to high-A, which was his breakout season. The dude was obviously a hulk (6’3″ and either 210 or 290 lbs, depending on what site you trust most), but given the level of competition and his age I guess it wasn’t that alarming he hit 28 home runs that year. He did make the leap to Double-A and Triple-A the following season as a 23 year old and hit 27 home runs, but racked up 179Ks in doing so. Without seeing so much as a single highlight clip of his, my immediate assessment was that I bet he couldn’t handle breaking pitches. Either that or he had no bat control whatsoever; if he was lucky enough to hit it (regardless of pitch), it usually went out of the park, but hitting it was the tricky part.

It goes without saying that steroids weren’t nearly at the forefront of my mind 9 years ago as they are now. Looking at his stats today, that’d be my first guess, fair or unfair. His power numbers dropped severely his last season in Triple-A, and he was essentially out of baseball after that. Maybe after having two pretty good years on ‘roids, he got off of them, thinking his own talent would make up the difference, only to discover he was wrong. Or maybe he was clean, but did have an injury, one that sapped his power; a bad back, wrist trouble, knees. Maybe he ate his way out of the game… Baseball Cube lists his weight as 210, but B-Ref lists it as 290.

Or maybe he just couldn’t hit a curveball.

But he had two pretty good years in the minors for someone with his skill set… he was never going to be Tony Gwynn, but he might have had the chance to be Rob Deer or Pete Incaviglia. Whatever the reason, he was good, but just not good enough. And while there’s failure in that, I wonder if he looks back and thinks for a summer or two he had it… no matter what he’s doing now or who he has become, he had it, and I wonder if that makes him feel satisfied or empty.

A wise and thoughtful man once said (and I’m paraphrasing), “Those who are blessed with just an iota of talent are actually cursed.” I mean, better not to be talented at all, if your iota isn’t going to be enough to actually take you where you want to go. All that iota does is make you aware of your own shortcomings. The untalented stroll around in ignorant bliss. The truly talented shoot across the sky like a comet and the in-betweeners look up at them from back porches, beers in hand, faint smiles on faces.

I’m an HR recruiter, and one of the more fascinating things about my job is to see what brought people to where they currently are, professionally speaking. Partly because it’s my job, but mostly because it’s a story. I see dozens of stories each day. Often I have but a piece of paper from which to discern the clues, but occasionally I meet the most qualified of these folks and get to chat with them about their story. I’d do this for free (ask some of my friends, they know this all too well), but getting paid for it is one of the few instances of my own professional life dovetailing with my wants. Hearing these stories gives me hope. Why? Because they are usually haphazard. They are not meticulously planned, even those that are among the most successful. We are not drones, organisms born from hexagonal chambers and shuffled off to our destinies from the moment of birth.

The biggest quirk to these stories? Oftentimes, what we are best at is not what we are paid to do. Or rather, maybe we are better at getting paid well for something heretofore unconsidered. Nobody grows up thinking, “Someday I’m going to make people think I’m really indispensible,” or, “I’m going to network with the best of them.” It’s bullshit work and should hold no value in a decent society, but it is a valuable skill nonetheless. As valuable as showing up every day and showing up on time, things anybody should be able to do. But not everyone can, and fewer people do.

Hitting straight fastballs thrown by go-nowhere pitchers three years younger than you? Writing navel-gazing drivel on a blog? Fly fishing? Not everyone can or does these things either, but these are not commodities. Just because you’re better at it than the average cat doesn’t mean anything. It’s not something that can be pursued on a professional level. But what if it’s what you’re best at? And all your eggs were in that particular basket, but it’s just not good enough?

Better to be a number-cruncher, no? The drone? The worker who gets things done, just because that’s what they were born to do?

Probably.

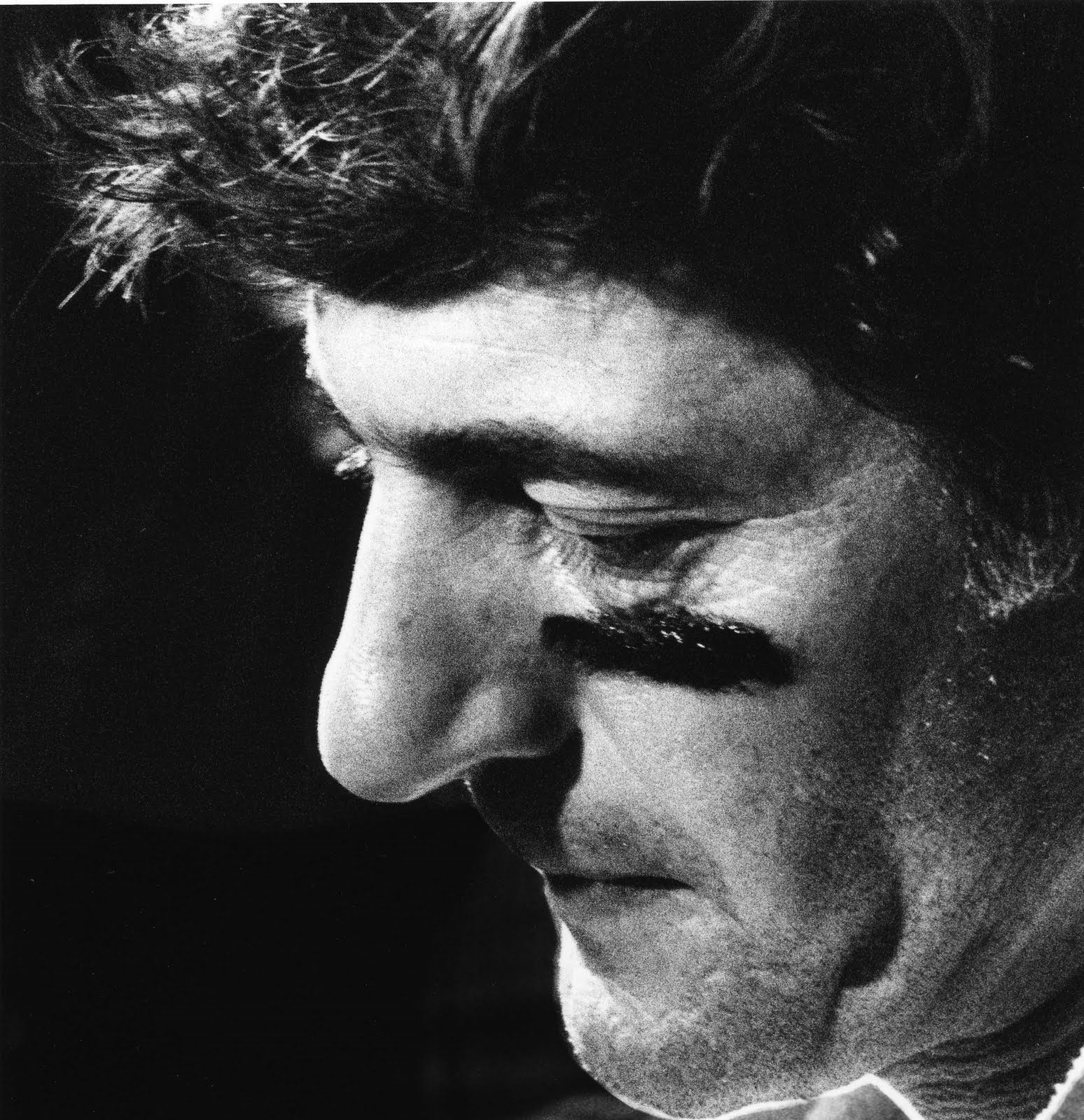

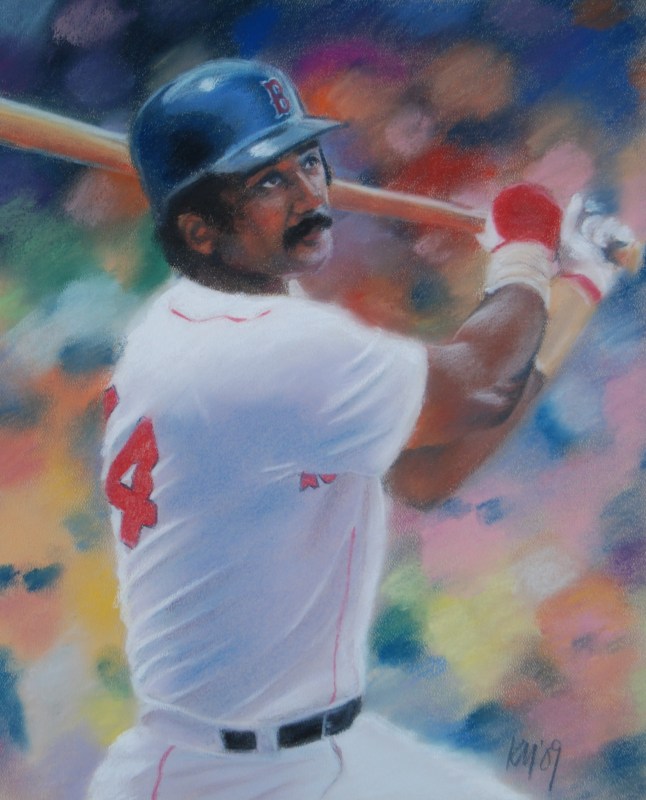

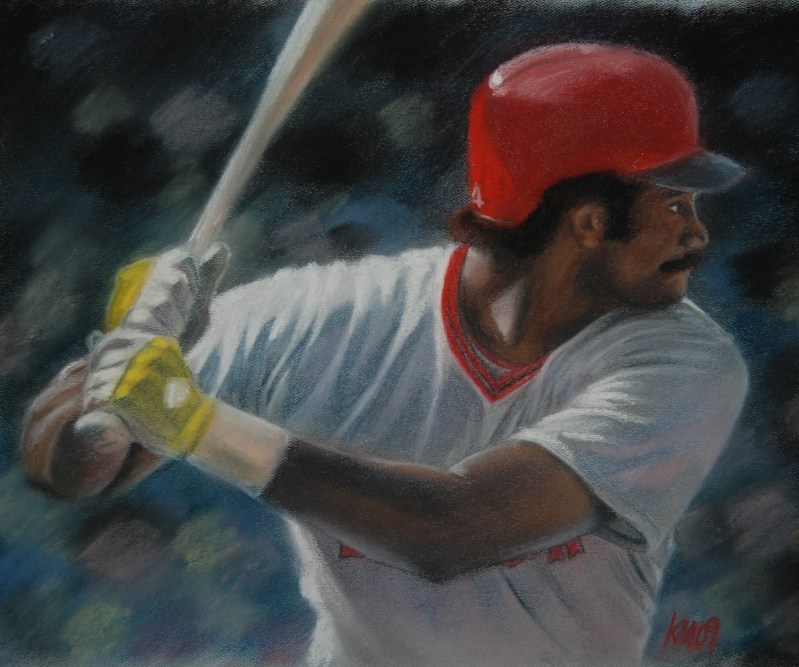

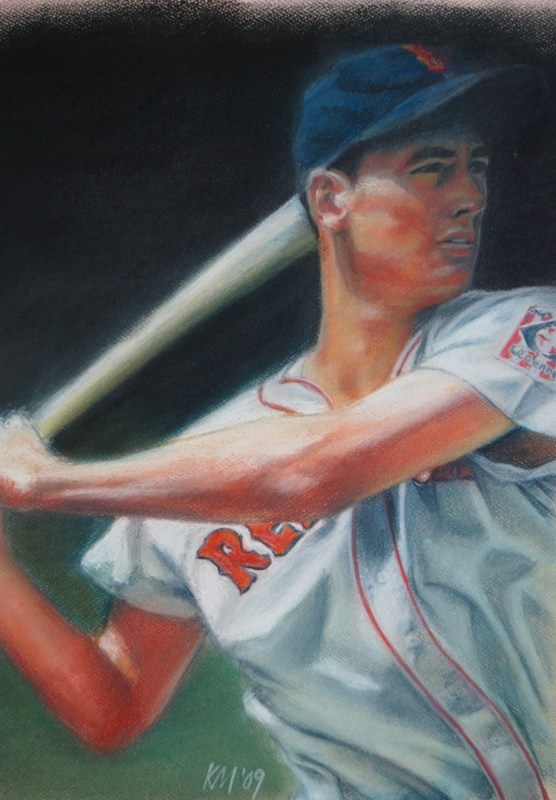

But there’s an art to this uselessness. Because whether or not the former second-round pick thinks he gave it his best shot, or if his stomach curdles up every night when the lights go out as he thinks about missed opportunities, he should be able to look back and think for a brief summer or two he was one of the best at doing what he wanted to do. Or at least the best of what he could do. The swing of the bat, connecting so forcefully on the sweet spot that it almost feels like you’re swinging through air as if you hit nothing, the ball arcing through the muggy air, dusky in the setting sun. Rounding the bases. I did that.

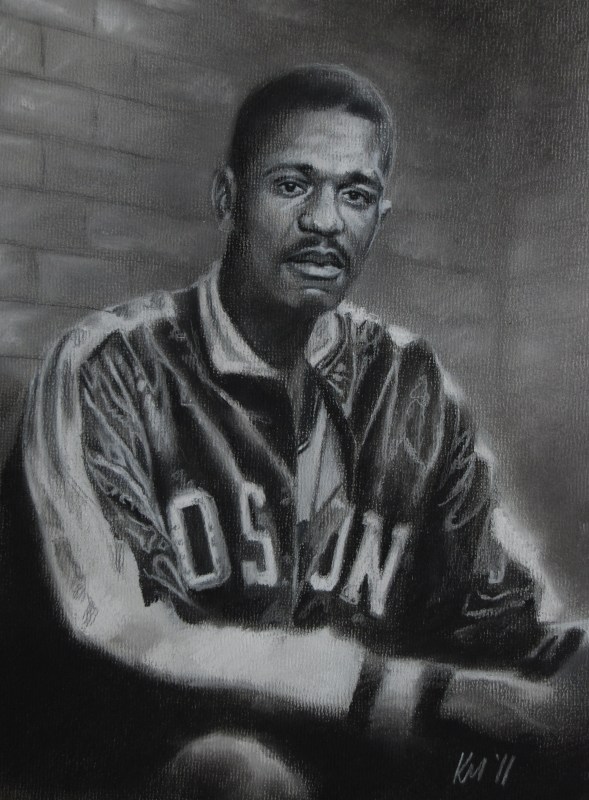

Putting a baseball where no man, not even Willie Mays, could ever catch it. Doing it a lot, even as the shadows grow ever longer on your career, closing in, the writing on the wall in permanent ink despite your hammering pitch after pitch over the fence. Because what else are you supposed to do? Give up? Even though your fate has been decided? Walk away? No. You do what you do, and see what happens.

Eventually the end happens. Everyone hits their ceiling. Few have the benefit of having it defined so clearly in columns of statistics.

And when the numbers tell you you’re done, you hang ’em up. Take your bonus money and maybe go start a construction business. Someone somewhere looks at your story, your resume, and sees some zigs and zags and wonders, “I’d like to hear that tale.”

Why?

Because it’s in all of us. Whatever you’re best at sucks, and you have to work the diagonal to find your way in the world, and people like success stories. Makes the impossible possible. But the iota of talent is like a childhood pet; a fond yet dim memory, kept on call for when it’s needed. You grill burgers and dogs in the backyard, sun on your face, calm in knowing that you had Something once, however fleeting.

Or maybe you live a life wracked by regret, wondering what could have been. Not even over never making it to The Show, but simply wondering why you were given a gift that could only bring you so far, in a career path that dictates failure unless you break through that envelope. Or maybe you had the Real Deal gift but your body betrayed you, even in your youth; a 24-year old man with a torn tricep, or a slipped disc. Or maybe you took PEDs, and if so, well, I don’t know. I don’t know.

Or maybe, just maybe, you really weren’t good enough, no matter what. In fact, that’s likely. There were people out there better than you at what you did. Better at trying to beat you. And what do you do then, after getting punched in the mouth, your teeth rattled, blood welling under your tongue? You better do something, that’s for sure.

We all have to do something.

Tags: Baseball, Life by Kevin

No Comments »