Complicity.

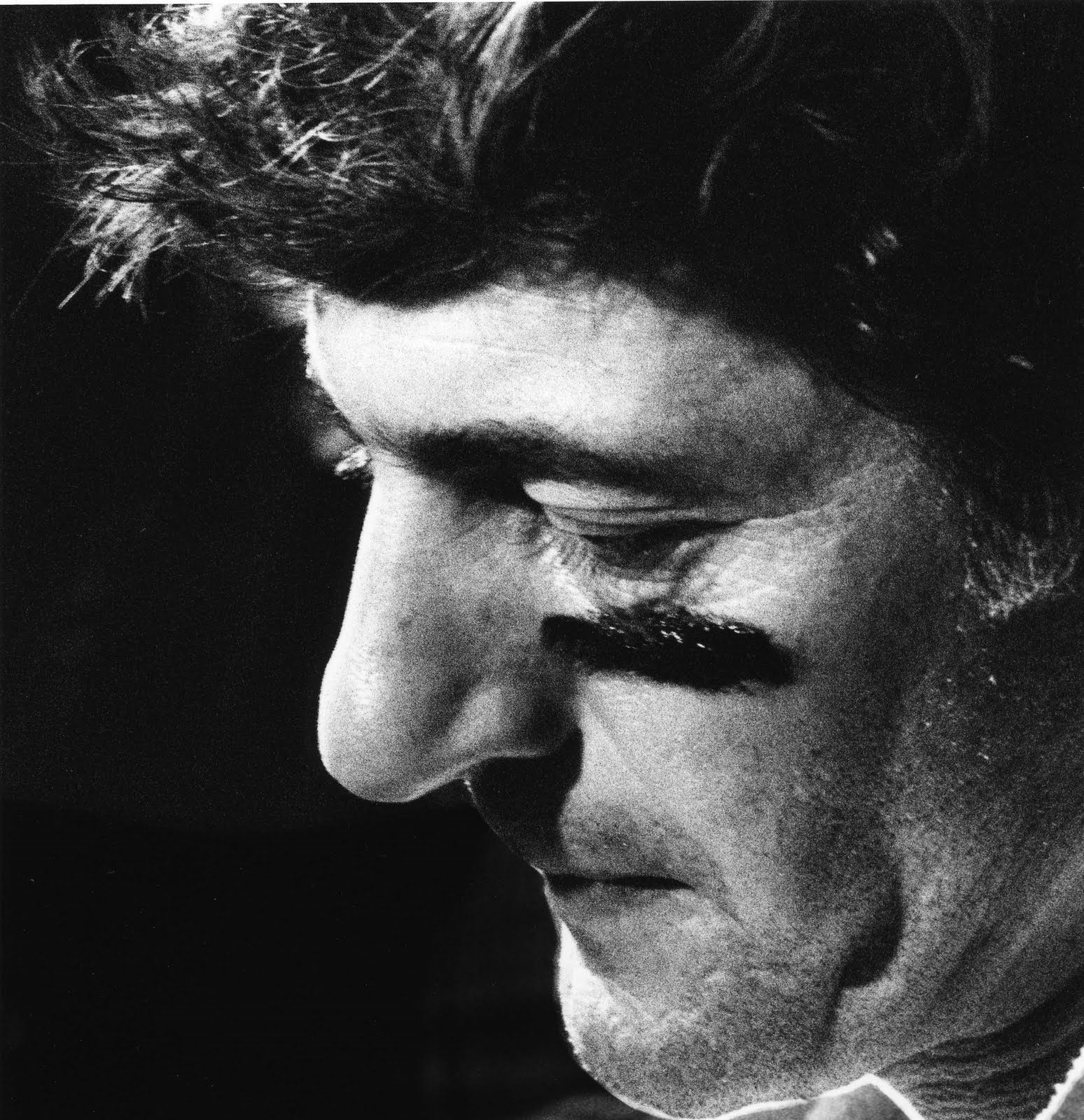

What was my father thinking to himself as I sat hunched over in my bed, my face buried in the crook of my arm, failing miserably at not crying?

I could almost hear him: I did this to him. Like if he had been a reformed alcoholic who watched me take one drink too many and careen into an endtable, lamp flying, me muttering to myself, “Who put that there?” That flawed gene, that came from me. This is all my fault. Years had slipped by where it had seemed there would be no repercussions, no piper to pay. Maybe the bullet had been dodged. But no, no… not on this night.

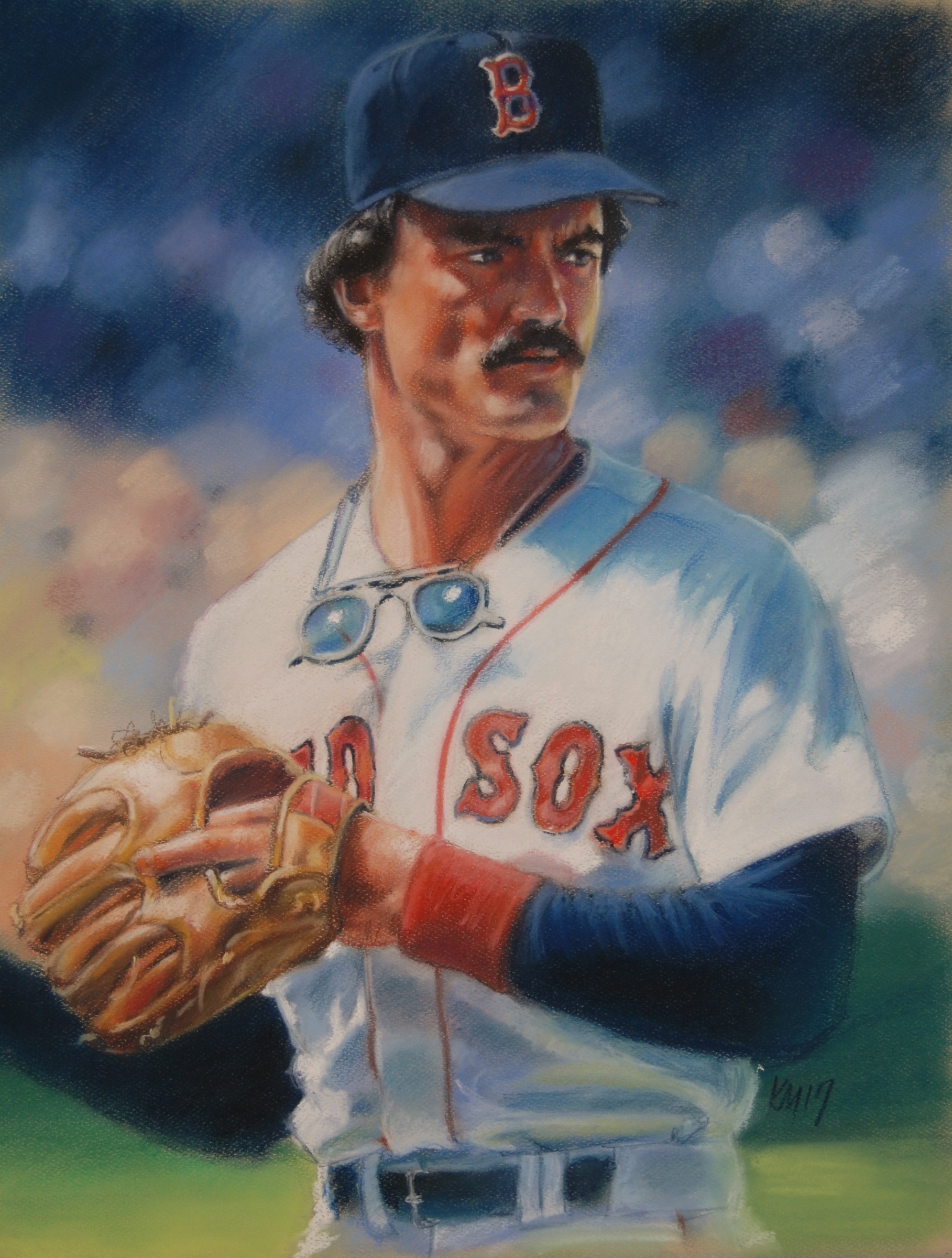

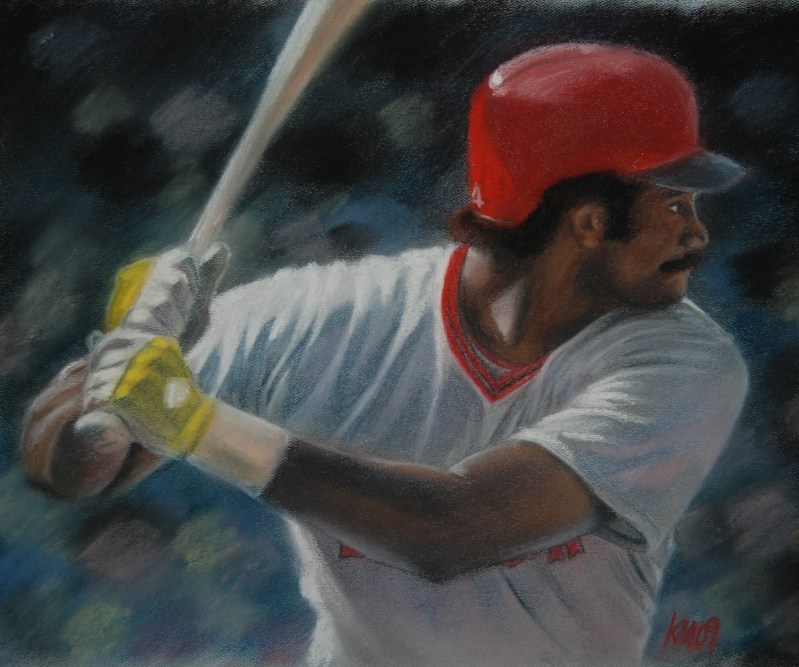

October 27, 1986. The Red Sox had lost Game 7 to Mets, my first dance with the fickle mistress of postseason baseball (I was fifteen). I had made it through the aftermath of Game 6 OK, angry as hell, of course, but with jaw set and focusing on the fact that there was still one more game to play. So what the hell was happening now?

I had stepped across that Sox fan threshold and finally understood what it meant to live and die for this team. And there I was, fucking crying, and I couldn’t control it and it wasn’t fair and I didn’t know why I had to feel this way at all. I had thought I held it together in the immediate wake of the final out, just morosely slinking off to bed, but once the darkness settled in and the reality of days without any more baseball and the tortured joke of how it all went down caught up to me, and it happened. I cried. Like each breath was being torn out of my lungs. I was fifteen, for Christ’s sake, but I still couldn’t help it.

And my father came in, and I wouldn’t look at him, I kept my face smashed into my arm as if this would somehow deny the reality of what was happening, and I think part of him had to be wishing he never nurtured my love for the Sox in the first place, never took me to games when I was very young, never sat and talked baseball with me, as if all of this could have been avoided if I just never cared about it to begin with. Complicity.

His words to me weren’t historic, not bathed in the glow that inspires orators, but they were pragmatic and heartfelt. There would be next year, he assured. He was careful to point out that my grandfather, his father, had followed the Sox for his entire life without seeing them win a World Series, and we had to appreciate what was given us (Poppy had passed away in 1983).

But it didn’t help, not at the time. And despite my grief over this love for a team that my father had passed down to me, despite his own role and accountability in what I was feeling at the time, I think he was proud. Because I cared that much. Cared too much, in fact, although that was really an impossibility, when you think about it.

* * *

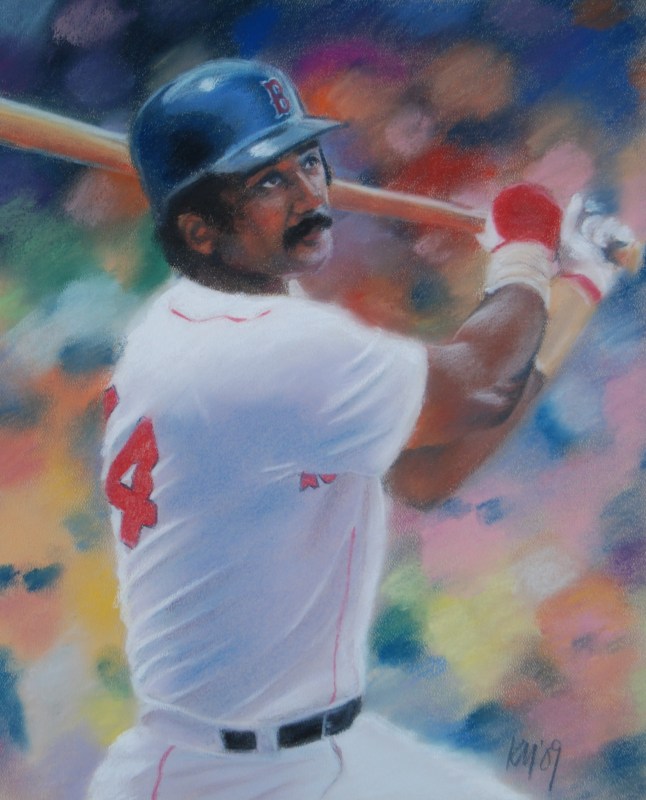

Scott Rolen had just flied out to right field, making the first out in the bottom of the ninth. I told my wife to go get our five-month old son out of his crib and bring him down for this.

“Can’t you wait until there’s at least two outs?” she asked.

“Edmonds might hit into a double play.” Pujols was on first.

She went to go get him.

There were maybe sixteen people in a room that was designed to seat 6. Kitchen chairs had been brought in, people were sitting on the arms of couches. I had driven two hours from my home in Maine to watch Game 4 at my sister’s house in Massachusetts, weeknight be damned. My wife didn’t quite understand why, just as she didn’t understand what was to be gained from waking an infant to witness a moment he wouldn’t possibly ever remember. But I had to watch the game with my dad. I had to be with my dad. And my son had to be there, too.

I sat on the floor at my father’s feet. He had the corner of one of the couches. We were faking being at ease, but not overly so: even false hubris would smack of the preconceived notion of celebration, therefore taunting the baseball gods.

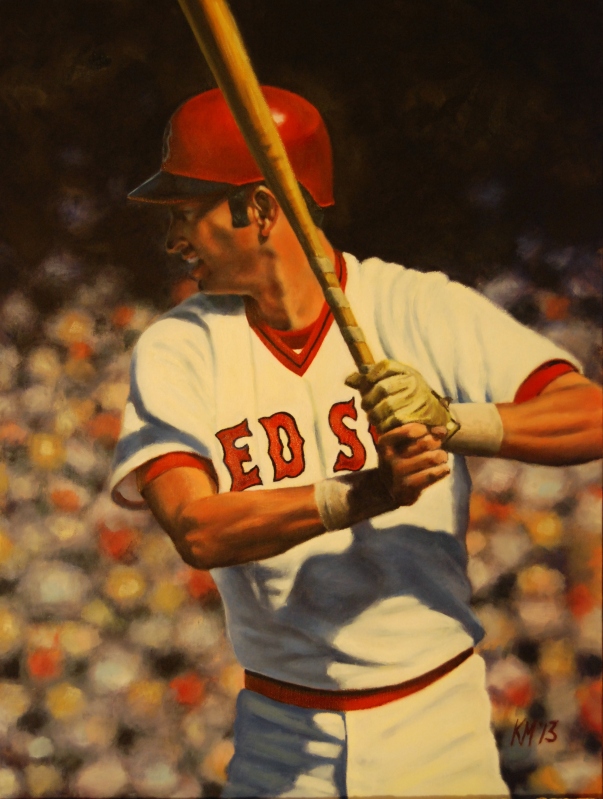

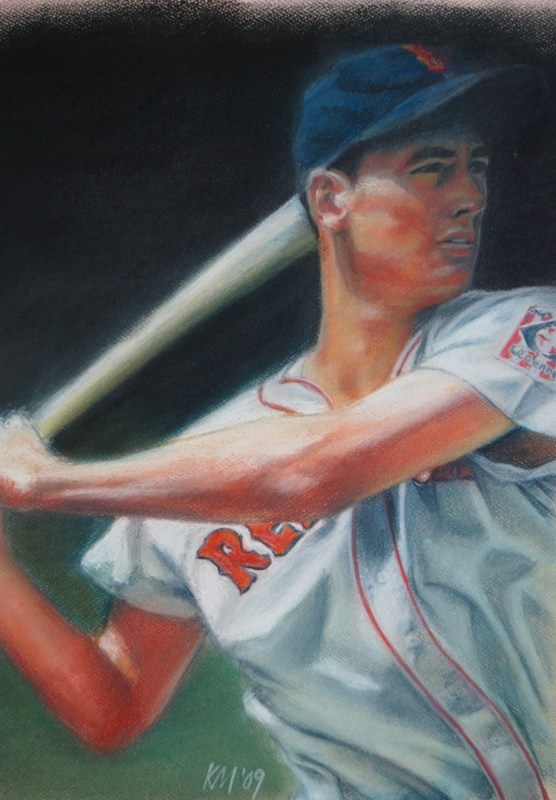

Back in the top of the third, when Nixon got to a 3-0 count with the bases loaded, we both simultaneously muttered, “I bet he’s got the green light on this pitch.” And indeed he swung, missing a homer by a few feet and scoring Ortiz and Varitek in the process. And the game progressed to its preordained conclusion, but you still had to wait for it to get there. And in waiting, you start thinking of all the ways that things could go wrong. But then it gradually became clear that none of these bad things were going to happen, and the Sox were indeed going to win the World Series, but you had to wait that interminable moment or two until victory actually arrived. Because baseball does not run on a clock. You had to get the outs.

Such anticipation regarding the Sox was audacious, considering their calamitous postseason history, but then again, the Cardinals were fucking cooked. Absolutely dead, and it seeped out of their pores the entire game. We could smell the stink of it in Hopedale, halfway across the country.

So in the bottom of the ninth my wife stood in the living room cradling my stirring son, and once Edmonds struck out, I shifted from my sitting position to a kneeling crouch. I threw a glancing look back at my dad, wondering what was passing through his mind, and saw that while his face was one of guarded calmness, he was grinding his palms together with such force that the veins on the backs of his hands stood out. And my eyes flitted back to the TV, intently watching Foulke face Renteria, and as soon as the hopper back to the mound was stabbed, the room erupted. Me leaping out of my crouch and instinctively grabbing my father, burying my face in his shoulder as I once buried it in my own arm on another October night long ago, crying just as I did then but for entirely different reasons, a long journey that we had taken together finally having come to fruition.

I held him for a lot longer than I care to admit. The embrace had its origins in baseball, but it became an opportunity to silently thank him for everything he’d ever done for me, to simply show him how glad I was that he was my father. He who had handed down to me this wonderful gift, wrapped in horsehide and red stitches.

When I finally let go of him, my wife put my bleary-eyed son in my arms. He was not crying. No, his face bore the serene look of the starsailor gone through the other side of a black hole, beholding a new universe, one where it just so happened that the words Dent, Buckner and Boone held no weight, nor would they ever. And I gently brought his forehead to my dampened cheeks, baptizing him into this strange and euphoric unknown.

Tags: Life, Red Sox by Kevin

1 Comment »