Becoming Dewey

Anyone who gets drafted by a major league baseball club is clearly gifted far beyond most of his peers. If he defies all odds and actually makes it to The Show, he’s proven that he’s one of the best several hundred baseball players on the planet at a particular moment in time, no matter how he ends up performing at that level. Surely there’s some solace in that for those who don’t stick around for very long, or even for those who do but never quite meet the potential they were blessed (or cursed) with. Yet darkened corners of taverns and the internet are filled with people who often ruminate on what might have been, what could have been, what should have been. Fulfilling the American stereotype of living a life without a second act; beating on, boats against the current, borne back ceaselessly into the past.

Dwight Evans made his major league debut as a 20-year old with the Boston Red Sox late in 1972 after winning the International League MVP at Triple-A Louisville that season; a tall, rangy prospect with a great glove, a cannon arm, and some pop in his bat. He spent the rest of the decade trying to fulfill the promise his potential, living up to it in stretches, but battling inconsistency at the plate and a string of various injuries that kept holding him back. But even as he struggled with his hitting, his defense always shined, most notably when robbing Joe Morgan of a home run in the 11th inning of Game 6 of the 1975 World Series, then immediately whirling to fire a throw to first to double up Ken Griffey, keeping the game tied as it headed towards its stunning climax.

By the turn of the decade, Evans had settled into a solid if unspectacular career, winning 3 Gold Gloves for his work in Fenway’s vast right field, averaging 15-20 home runs a season and batting around .260 every year, give or take some percentage points. He was 28 years old in 1980, his closest contemporaries in terms of performance being the forgettably serviceable Sixto Lezcano and Rick Monday. After a particularly brutal start to that season, Evans was batting a paltry .194 with 5 home runs and 22 RBI by the All-Star break, eventually being platooned with Jim Dwyer in the process. He needed a change, and to his credit, he sought one out and embraced it.

Red Sox hitting coach Walt Hriniak, a disciple of famed hitting guru Charlie Lau, taught Lau’s theories to Evans: incorporating a balanced stance through rhythm (in Evans’s case, a toe tap), followed by a dramatic weight shift mid-swing, then ensuring full arm extension through the swing by releasing his top hand as he finished.

The change in approach worked, and Evans improved his .613 first-half OPS to 1.001 for the second half. He kept this torrid pace going right on into 1981, tying for the league lead in home runs with 22 during that strike-shortened season and finishing third in the MVP race. As important as tinkering with his hitting mechanics was, Evans also began utilizing a more patient approach at the plate, leading the league with 85 bases on balls (the first of three times he’d take the title that decade), setting him on the path of becoming not only a slugger but an OBP machine. This relatively rare combination of skills led to him batting leadoff at times throughout the mid-to-late ‘80s, including an at-bat where he crushed the first pitch of the 1986 major league baseball season for a home run on Opening Day.

His continued to dazzle in right field as well, winning 5 more Gold Gloves throughout the decade (bringing his total to 8), not to mention staking several claims to the unofficial Runners Held crown, so foolhardy it was to test his howitzer arm by trying to take an extra base on a ball hit to him.

He seemed ageless, racking up 100+ RBIs in 1987, ’88 and ’89 as he cruised into his late thirties. But back troubles began to hamper him during this time, gradually sapping his power and reducing his world-class range in right, necessitating a shift to first base and DH as his career began to wind down. After a lackluster 1990 campaign in which he hit .249 with 13 homers with 63 RBI, he was unceremoniously released by the Red Sox at the age of 38. Wanting to go out on his terms, Evans signed with the Orioles and turned in one season for Baltimore, retiring at the conclusion of 1991.

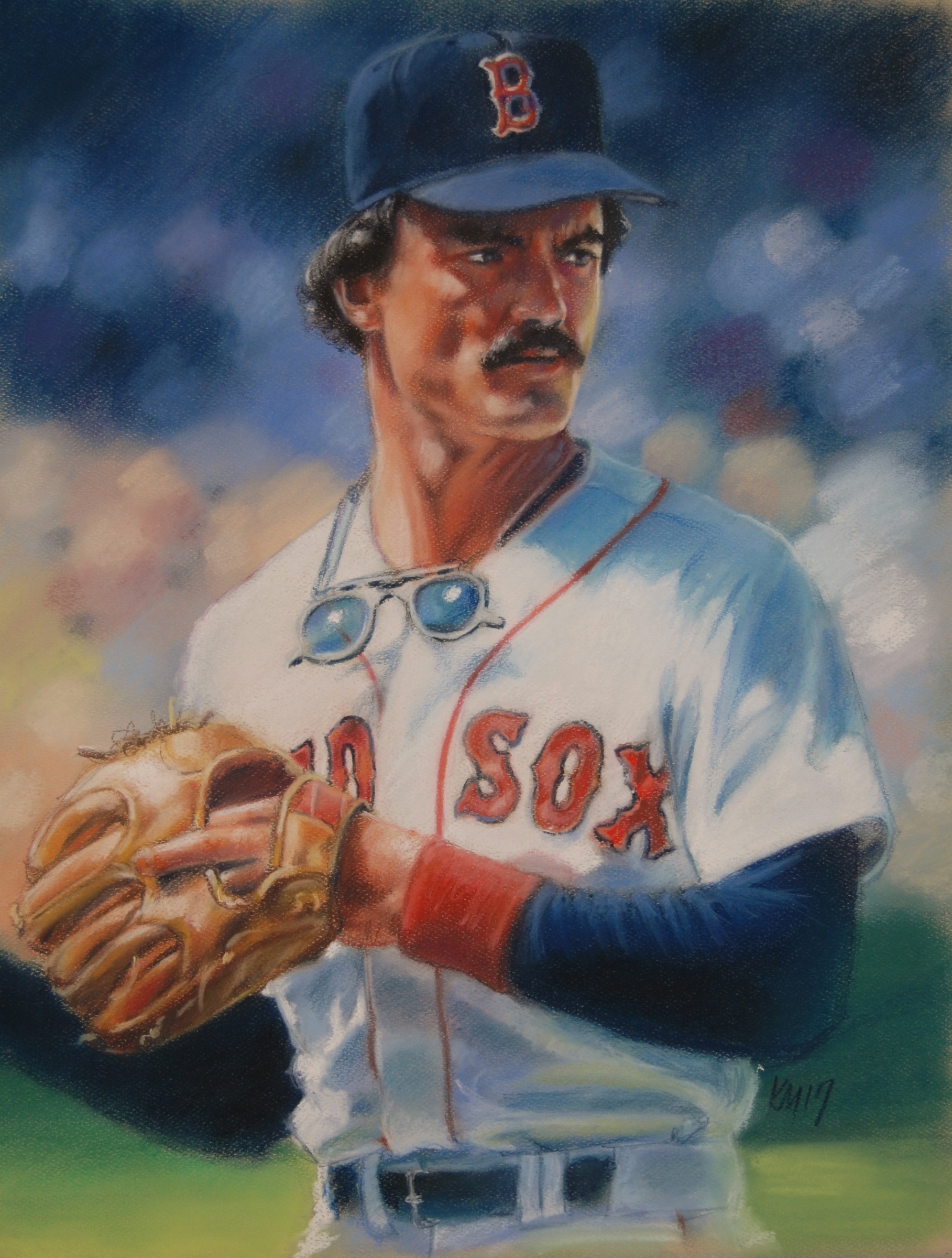

Gone are the heady days and neon nights when Evans roamed the vast acreage of Fenway’s right field, Tom Selleck ‘stache making the ladies swoon as he crushed first pitch fastballs into the bleachers, trotting the bases with that crouched gait. High above the patch of grass that Evans patrolled so magnificently without peer hang the numbers the club has seen fit to retire; ironically, his is not among them, even though it should be (certainly more than Fisk’s or Boggs’s, although number retiring is not a zero-sum game).

There was hope that Evans might receive some long overdue credit once he reached eligibility for the Hall of Fame in 1997. He was not close to being a slam-dunk candidate by any means, but it was possible to envision a slow and steady climb up the ballot over a period of years, culminating in election sometime in the mid-‘00s. You could make a strong case that he was the best player in the American League for the entirety of the ‘80s, to say nothing of the X-factor his game-changing fielding provided. Bill James, among others, has championed Evans’s Hall of Fame credentials. Alas, he dropped off the ballot after 3 years, peaking with a paltry 10.4% of the vote on his second ballot in 1998, a victim of the burgeoning steroid era and his own late start in shifting his career to a higher gear.

Yet here was an American life that had a second act, however improbable it may have seemed. That old-timer at the end of the bar can take heart in a living example of someone who actually Turned It Around, and therefore rightfully hope for the possibility of it happening again with someone else. Maybe even to himself. Anybody can do anything, as long as you decide you want to. And follow Charlie Lau’s theories. And look like you should be wearing a Hawaiian shirt and driving a red Ferrari in the process.